Since I became a metalhead several years ago, I have read a lot of books. This unexpected benefit of my renaissance will come as no surprise to seasoned metal fans, because heavy metal’s intimate connections with literature are well-known and well-documented, almost to the point of cliché. Whole books in themselves could be written about the impact of Tolkien and Lovecraft on metal; there are multiple academic papers examining Iron Maiden’s adaptations of lyric poetry, Metallica’s interpretations of Hemingway. As a metal journalist, a significant proportion of the albums that come my way for review are directly inspired by books.

But why? Why does this much-maligned genre of music, so often ridiculed and assumed to be low-brow, have such a rich and complex relationship with literature? Why are there whole college courses devoted to teaching English literature via the medium of heavy metal? No other type of music, even classical, has such close associations.

Could it simply be down to the vagaries of chance? In the 60s and 70s the founding fathers of heavy metal shared a fascination with the works of British occultist Aleister Crowley. Jimmy Page, Ritchie Blackmore, Toni Iommi, Geezer Butler; they all read Crowley, and this fed into the lyrical themes particularly of Black Sabbath, who rehearsed in a castle dungeon, employed the evil-sounding tritone and heavily down-tuned riffs, as well as the satanic imagery to match. Their influence perhaps set heavy metal on the dark path towards horror, religion and the occult which black metal continues to explore.

And then came Iron Maiden. Arguably no other bands have had such an impact on so many subgenres of metal, and Maiden’s enterprising, educated approach to lyrics is legendary. Coleridge, Tennyson, Homer, Shakespeare, the Bible; throughout their career they have mined history and literature for song themes, and rather than simply quoting or referencing great works, they explain, abridge and interpret. Attending an Iron Maiden concert is an incomparably rich cultural experience, often humblingly so.

Another of metal’s most influential bands, Metallica, also composed literary adaptations from early on in their career. ‘For Whom The Bell Tolls’ is a simple re-telling of Hemingway’s classic, while ‘One’ is an adaptation of Dalton Trumbo’s 1939 novel ‘Johnny Got His Gun’, powerfully evoking the horrors of the First World War. Kirk Hammett’s love for all things horror is well-known, and ‘The Call of Ktulu’, about the mythical tentacled monster from the edge of space and time, is at the heart of metal’s veneration of HP Lovecraft.

There’s no doubt that a few individuals can have a profound effect on a culture, steering it in a particular direction. And in the 1980s Tipper Gore weighed in, with nine out of the fifteen songs on the PMRC’s (Parents’ Music Resource Centre’s) ‘Filthy Fifteen’ list of objectionable lyrics being metal. Meanwhile Judas Priest and Black Sabbath were both forced to defend themselves in US courts, accused of encouraging the suicides of young fans with their so-called satanic messages. Dee Snider’s legendary taking down of Tipper Gore at the PMRC Senate hearing showed that metal could hold its own intellectually. But the damage was done, and the inanity of hair metal’s misogynistic antics and banal lyrics didn’t help metal’s reputation. Even affectionate satire such as Spinal Tap ridiculed metal for its silly appropriations of historical themes; for example their facile recounting of the story of Stonehenge, replete with leprechauns.

So are heavy metal’s literary borrowings just pomposity? The attempts of low art to imitate high art, basking in the reflected glory of a prestigious discourse in order to confer legitimacy? No, because as a counter-culture, metal places itself outside the spectrum of high or low art. Mastodon singing about Herman Melville can perform on the same festival roster as Municipal Waste singing about beer and sharks, and be judged with the same merit. There’s no doubt that there is plenty of grandiose theatre and showmanship in metal performance. But there is also a huge proportion of metal bands that eschew any sort of image or showmanship whatsoever; it’s all about the music and the message.

Maybe all these literary references are down to the educational levels of metal musicians and fans. The anthropological study of metal has come a long way since Deena Weinstein’s analysis that it’s a blue-collar subculture, born out of the process of de-industrialisation and the frustrations of the disempowered working class male. Recent surveys have delighted in reporting that metal fans are drawn from all sections of society and that what tends to unite them is a high intellect, as well as an introverted character.

But this analysis makes me a little uncomfortable, and metal does not define itself in this way. Metal remains, and always will be, the music of the outsider, the misunderstood, the oppressed. And in any case, educational level does not necessarily correlate either with intellect or being well-read. I went to a top-tier university where I met some exceptionally stupid people doing exceptionally stupid things. My grandfather left school at twelve and was the smartest and most well-read person I ever knew.

For me, it’s the musicology of metal that explains its literary associations; specifically, the complexity of metal music’s affective range. The two main musicological factors that define metal – distortion and the power chord – have such a complex effect on the human nervous system that metal is able to evoke complex, deep, subtle emotions that lend themselves to story-telling. Distortion is the sonic effect created when amplifiers are played at too high volumes, and it has a visceral effect on the human brain. Distortion generates higher frequency energy by clipping the signal and therefore the waveform, emphasising the higher frequencies and giving the impression that things are closer than they really are, enhancing the idea of something looming, a perception of heaviness. The power chord, meanwhile, is simply a two-note interval played on the electric guitar, but when combined with distortion, additional sounds are generated at the sums and differences of the frequencies of these notes’ harmonics. These are called resultant tones, and only a symphony orchestra or a pipe organ can replicate this intricate aural identity. It’s no coincidence, then, that the only other type of music as influenced by literature as metal is classical music. The orchestra and the metal band can convey meaning and a sort of synaesthesia in the active listener. Add to this blastbeat drumming, growled vocals and the use of modal scales, and metal is able to recreate anaphonic representations of non-musical phenomena like no other music: the sounds of industry, weather, space, inhuman voices. Iron Maiden’s renowned guitar ‘gallop’ is used to convey the sounds of horses’ hooves on the battlefield in ‘The Trooper’; Nile uses the ominous dissonance of the Phrygian and oriental scales to evoke ancient Egypt. More than any other musical form, metal is able to tell stories, and it yearns to do so.

So metal music is rich, complex, technical, played by the highest level musicians to the most discerning, active listeners. But there’s something else involved too. Heavy metal is more than music; it’s a subculture and this means it is all-encompassing, with the extramusical factors – the album covers, the lyrics, the clothes, the values – all part of the overall conception of the work. In this sense, metal follows in the romantic tradition of writer-artists such as William Blake, Dante Gabriel Rossetti and others for whom the words and pictures were one and the same. The metal album cover art is of prime importance; indeed many artists (such as Paul R Gregory, Dan Seagrave, Eliran Kantor) specialise in subgenres of metal cover art, and underground bands often design their own covers as a matter of pride as well as economic necessity. The status of cover art is shared with the fantasy genre of literature; another non-visual art form in which imagery is of prime importance.

Ironically for a type of music in which the lyrics are often unintelligible to the listener, they are also of prime importance to metal. Recently I interviewed Power Trip’s Riley Gale and he spoke about the prevalence of allegory and metaphor in metal lyrics, and how they should be judged as poetry. Karl Sanders puts extraordinary research into Nile’s ancient Egyptian lyrics, and his lengthy, explanatory album liner notes are demanded and treasured by Nile fans.

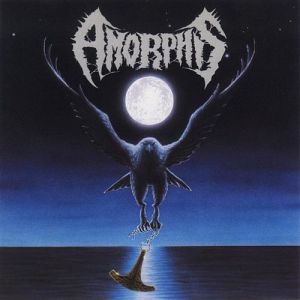

As a subculture, metal often takes on the characteristics of its country or locality, incorporating local instruments, sounds and folklore. Consequently folk texts play a central role for many metal bands, particularly from Northern Europe. Amorphis is one of several Finnish bands influenced by the Finnish epic poem the Kalevala, while the Poetic and Prose Eddas (the sacred texts of Old Norse mythology) run deep throughout both black metal and Viking metal.

Metal can be viewed as a quasi-religion with a canon of its own, and that canon includes Tolkien, Lovecraft and Stephen King. For metal fans, metal is life, and when they read a book they wish to connect it to their music. But what about the metal musicians? The greatest artists don’t like to talk about their art; they prefer a studied ineloquence. Many of the metal bands I have interviewed as a journalist have clammed up modestly when I ask them about their creative process, and answered with a shrug to the effect of ‘It is what it is’. So perhaps my analysis here is as affected as Dimmu Borgir’s wardrobe or Alice Cooper’s stage set. But there’s no doubt that metal’s extraordinarily fruitful collaborations with literature will continue to enrich.

The Most Metal Of Books

Not all works of literature lend themselves to metal. It’s unlikely we’ll see a thrash adaptation of Jane Austen or Thomas Hardy any time soon. But when a dark story cries out to be told musically, metal bands have got you covered… here are just a few.

1) The Bible. Woe to you O Earth and sea… sneers the intro to Iron Maiden’s 1982 classic The Number Of The Beast. Where would metal be without the Bible? Endlessly plundered for band names, themes and lyrics. The Book of Revelation alone is a sacred text of our gloriously blasphemous subculture.

Listen to: Iron Maiden, Deicide, Rotting Christ, Impaled Nazarene

2) The Lord Of The Rings, by JRR Tolkien. Tolkien’s epic three-parter is another sacred text of metal, beloved by subgenres from power to sludge. Another author who has provided countless band names, but notable song and album adaptations have been by Iced Earth and Blind Guardian.

Listen to: Cirith Ungol, Gorgoroth, Ainur, The Summoning, Blind Guardian, Iced Earth

3) The Call Of Cthulhu & Other Weird Stories, by HP Lovecraft. The unfortunate strains of racism in Lovecraft’s writing have not aged well, making him an uncomfortable read. But his influence is undeniable; the cosmic horror of HP Lovecraft is woven throughout metal, and there are a significant number of bands that only make music about their American gothic hero.

Listen to: The Lurking Fear, Nile, Revocation

4) Thelema, by Aleister Crowley. The C20th British occultist spawned a whole mystical belief system. The fundamental principle underlying Thelema, known as the “law of Thelema”, is “Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law. Love is the law, love under will.”

Listen to: Anaal Nakhrath, Devildriver, Marilyn Manson, Ozzy Osbourne

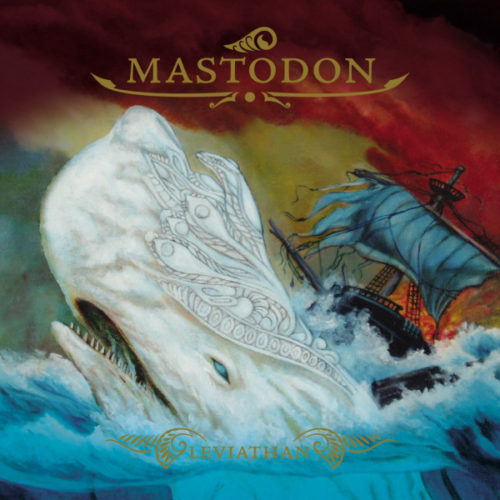

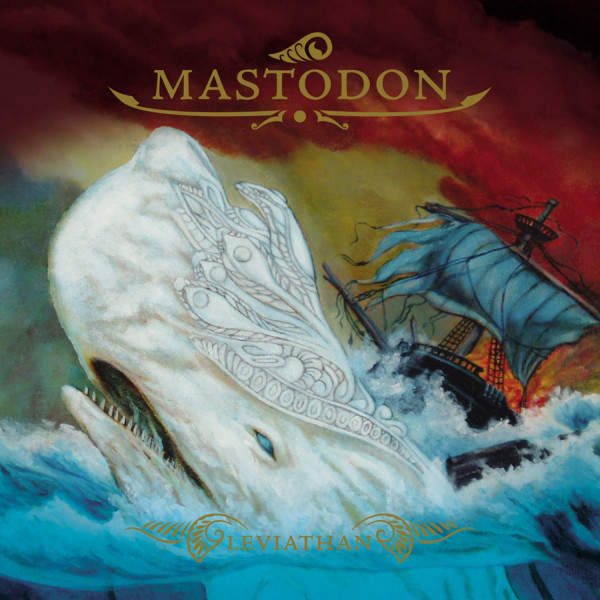

5) Moby Dick by Herman Melville. Mastodon’s acclaimed second album Leviathan, with its iconic cover art, is based on the classic 1851 Great American Novel.

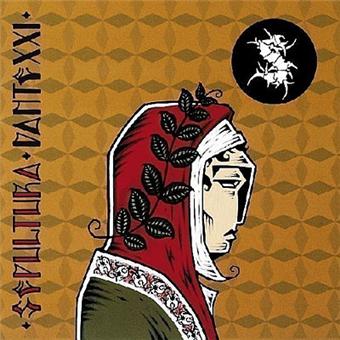

6) Inferno/ The Divine Comedy by Dante (C14th). You don’t get much more metal than Dante’s Inferno, or the Divine Comedy’s nine circles of hell.

Listen to: Sepultura, Eye Of Solitude

7) Elric of Melniboné, by Michael Moorcock. Hawkwind’s association with fantasy author Moorcock climaxed in their most ambitious project, The Chronicle Of The Black Sword, based around the Elric series of books.

8) The Marriage Of Heaven And Hell, by William Blake

Listen to: Carcass, The Human Abstract, Ulver

9) For Whom The Bell Tolls by Ernest Hemingway

Listen to: um, Metallica..

10) Dune by Frank Herbert. Colorado’s melodic thrashers Necropanther wrote a brilliant concept album (Eyes Of Blue Light) to this classic sci-fi novel. Check out Necropanther’s books column on this website!

11) Tristesse De La Lune by Baudelaire (1868). On their 1987 album Into The Pandemonium, Celtic Frost set the romantic poem to music in both french and english, providing a fascinating study in the links between music and poetry.

Which books and bands have I missed ?

Which other books should be made into metal albums?

Here’s my Literary Metal Playlist: it was very hard to choose…